Celebrating a fabulous Rijksmuseum Amsterdam purchase

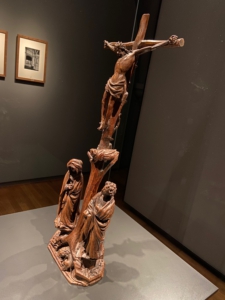

The Calvary group by Claus Sluter.

New in 2025: the object has been cleaned and more details are now visible.

Text: Drs. Kees Kaldenbach, copyright 2021

In March 2021 the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam purchased a dream object: a Calvary. It has been carved realistically in boxwood by – or under leadership of – Claus Sluter (born c 1350-died 1406). As a work of art it is firmly dated between 1389-1406 when Sluter worked in Dijon, France. The block of wood was C14 dated as having grown between 1318-1380.

Hereto largely unknown to the art world, the object was once in a collection of Canon Franz Bock in Cologne, Germany. After a later purchase it was presented by the Rijksmuseum to the world in August 2021.

One year before, in the spring of 2020, an art dealer in Munich Germany, on behalf of the owner, approached the Rijksmuseum and showed the images on a laptop to Rijksmuseum specialist Frits Scholten. After extensive research the decision was made to purchase for a yet undisclosed sum in the range of “seven zeroes” thus well above one million Euros. The Rembrandt Society fund supported the purchase with E 350.000,- Another art fund, the Mondrian Fund donated another large undisclosed sum, as did private individuals.

A Calvary is usually defined as a Crucifix statue of Jesus, plus two mourning figures: Mother Mary and John the Evangelist.

In this Calvary we see the image of a life-like warped tree trunk or “arbor crucis” out of which the cross has been roughly shaped. This tree – according to Christian faith – ultimately stemmed from a tree in the Garden of Eden, once planted there by Seth, on Adams grave.

The torso of Christ is curved in pain, of a heart breaking realism that we will not see again until the nude Adam painting in the Ghent Altarpiece by Van Eyck. Down to the left is Mary, dresses in a cloak with many curves, looking downward, standing on a six-sided pedestal. To the right John the Evangelist is looking up in and expression of grief. Midway down we see an angel who was once holding up chalice to catch the dripping blood of Christ’s wounds from his chest and feet. Christ’s head is crowned helmet-shape with thorns allowing the faithful to identify and relive that pain. All the way down is a scene, very rare in Christian imagery, of a lion’s den with two cubs. According to folklore and the book Physiologus the cubs were born dead and shapeless, being licked into life in three days. Philip the Bold, who ordered the sculpture, liked to use the lion as his heraldic animal. At the bottom we see acanthus leaves, a feature also seen in manuscripts of that time and era.

The boxwood has been C14-dated as being 1318-1380 and it must have been a big block of expensive wood because the sculpture has been largely cut out of a solid block. Ultra fine cuttings in boxwood would become a cherished object of desire, also in prayer-focusing objects to take on a journey. The Rijksmuseum now owns a series of these high-class micro woodcarving objects related to Christian faith.

Note that Claus Sluter was a trailblazer and his work was a giant leap forward (in iconography, in heavy folds in garments, in ultra realism); his work became the key inspiration for future grand masters like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weijden who created their dazzlingly realistic and almost photographic realistic works in Brussels, Tournai, Bruges and Ghent, (all Belgium) in the 1430s, thus about 30-40 years later.

Owning an original work by Sluter was on the ultimate wish list of the Rijksmuseum; to honour him since 1885 his effigy was represented all over, shown in one window and three times on outside walls. Etymologically his last name could mean key-bearer. He did not become chamberlain of the Duke but received various honorary extra money payments. His first name crops up in archival documents as Claes / Claus / Claus / Klaas.

This formerly unknown superb Calvary masterwork was once crafted by Claus Sluter himself or by a team of fine woodcarvers led by him. Sluter was born around 1350 in Haarlem (Holland) and was active as a craftsman-sculptor, soon to become one of the most influential court artists in the Burgundy court in and around Dijon, France.

This Burgundy court was a traveling high-maintenance and high visibility circus centered around the extravagant leader duke Philip the Bold (aka. In French: Philippe le Hardi ; in Dutch: Filips de Stoute), duke of Burgundy born 1342 and in power from 1363-1404. He was initially just duke of Burgundy and Artois (North-western France) and had his eyes set on acquiring Flanders and the upcoming counties up north of Holland and Zeeland through intelligent marriage liaisons. He also had family ties with the French king, but as a ruler he was actually richer and more powerful than the French King.

Born as the powerful son of French king John the Good, he married Margaretha van Male, Countess of Flanders, who was the sole heir of the last Count Dampierre, count of Flanders. With this wedding he married together Burgundy and Flanders without a drop of bloodshed. Philip thus stands at the beginning of a family succession line that would keep clicking more areas together by marriage and thus – in the end – succeeded to unify the Netherlands plus Belgium. That would lead up to the reign of the great European warlord and Emperor Charles V, active from 1515-1555.

Later in life, in order to pray and safeguard his soul, Philip the Bold supported a Charterhouse of extremely strict and poverty-adhering monks in the Chartreuse of Champmol just outside Dijon, the chosen location of his future grave. Above the Charterhouse high altar there was a fine triptych by Melchior Broederlam, born Ypres, Flanders, ca 1350 (+ after 1409). Thus he was of the same age group as Sluter and his best work is still in the museum of Dijon.

Stained glass window in Rijksmuseum, produced in England c 1884. Showing “Jan” Sluter as one of the eternal Dutch artist heroes of all time. Jan is purely a writing error in the process of ordering the stained glass.

Philip the Bold’s ultimate claim to eternal fame is that he recognized and hand-picked excellent artisans, master craftsman, now with hindsight seen as great gifted artists of international stature. He hired these craftsmen in order to glorify his own status and entourage and thus to make his large court ultra-famous and visible – also by creating ephemeral objects for feasts like flags and banners, and bigger objects to be used in carnival-type moving float presentations. Think of sails, coaches, wall paintings, and weapon shields… as physical objects they all are gone forever in the mists of time. All this extravagant bling bling meant attention from the international audiences and greater status and fame for Philip.

In present day art history the following four names are regarded as truly great artists; then they were just considered mere craftsmen whose work were not signed. But we find their names in the bookkeeping ledgers of duke Philip. Outstanding among the dozens are four names: sculptors Jean de Marville and his initial assistant Claus Sluter, who became workshop chief, and some years later on Sluter’s pupil Claus de Werve and finally se see court painter Jean Malouel (= Jan Maelwael). Sluter was given a mansion in Dijon with a workshop hall attached, where he was workshop leader and manager. This allowed the Duke to visit him from time to time to discuss projects. All in all some 200 workers “ymagiers” or image makers were around for shorter or longer periods of time – to work on all sorts of material: wood, stone, iron and lead, glass, texitiles, leather etc. The language used most frequently can be gauged from their first and family names in the bookkeeping, sounding mainly Diets = early Dutch, Netherlandish. Uniquely, the artistic wind blew down south from the Netherlands.

Philip the Bold’s court with all of its retinue was residing for weeks or months at the time in Brussels (now Belgium), and in Dijon (France) and had to show his dominance and presence in Flanders, Artois and Burgundy.

The big economic powerhouse of his empire was not located in Dijon, eastern France – but in Flanders with major bustling trade cities such as Bruges, Ghent, and the residential city of Brussels (all now Belgium).

The big industry was sheep wool import from England, turning it into high quality dense broadcloth or “laken” with a process of various weaving techniques and felting. This broadcloth was then exported all over Western Europe. Flanders soil was too wet to get successful crops of grain, and therefore various grains for making bread was imported, largely from France. Thus Flanders became the pivotal exchange point.

What is left out there of this great teamwork by the workshops of Jean de Marville and Claus Sluter ?

A great choice wild be to visite the Museum of French Monuments in the Trocadero palace opposite the Eiffel Tower, Paris.

Here we start with the ORIGINAL works just outside Dijon, France:

1. To start with the large Moses Well (Puits de Moise) now in the grounds of a Charterhouse hospital (Chartreuse de Champmol), rain proof enclosed in a circular stone structure, with glass panes, and thus visible to the public from the outside. This work is firmly known to be made by Claus Sluter, with archival proof of payment. It was both a well and a pedestal.

One may state it is a key work in Western art history.

Visible today is only the base (sockle / pedestal). On top of the pedestal was a Calvary which is defined as a crucifix holding Jesus with standing at the side his mother Mary and John.

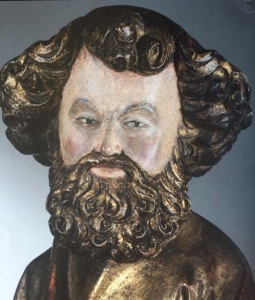

On the sides of the pedestal are these six life-size figures: Moses, David, Jeremiah, Zachary, Daniel, Isiah, all Old Testament characters who have announced the future Passion of Jesus Christ.

The angels placed above the work of Sluter are by his assistant Claus de Werve.

A restoration of the original sculpture carried out between 1999 and 2003 has shown remains of polychromy (coloration) which originates from 1402-1404.

One may state it is a key work in Western art history. Once it also had a large crucifix on top. Whether it also had figures of Mary and John at the base of the cross as well is a matter of conjecture. From 1927 and up to 1940, a life-size plaster cast of this pedestal with sculptures around was placed in the upstairs central front hall of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, opposite the Rembrandt Night Watch at the other far end of the central Gallery of Honour, forming the alpha and omega of Dutch art. This cast was later removed, for only original works of art were deemed admissible.

2.Two extravagant over lifesize funerary monuments now shown in the museum of Dijon, Musée des Beaux-Arts. These were seriously attacked over the ages, especially during the French Revolution of 1798 – but the series of Mourners or Pleurants wrapped around the base are still mostly there and a number of the Mourners are firmly ascribed to Sluter. The dormant large figures on top are later imperfect recreations based on drawings and prints.

3. Started by architect and master mason Drouet de Dammartin: The church entrance sculptures in Champmol, just outside Dijon, with lifesize images of Philip the Bold and his wife. Initiated by Jean de Marville and finished by Claus Sluter.

To the left hand side: Patron saint St John the Baptist and a kneeling Philip the Bold (1342-1404)

Central column: Mother Mary and Jesus child. Attributed to sculptor Jean de Marville.

To the right: kneeling Marguerite of Flanders (1350-1405) and her patron saint St Catherine of Alexandia. Initiated by Jean de Marville and finished by Claus Sluter.

The plaster cast of the Moses Well is now in the Musee des Monuments Francais and was made by Jules Fontaine and entered the collection in 1880.

The plaster cast of the Charterhouse portal entrance is now also in the Musee des Monuments Francais and was made by Jean Pouzadoux and entered the collection in 1885. Digital corrections to the plaster cast date from 2005, by Merindol.

4. Colouring these statutes was the task of the Burgundian court painter Jean Malouel (= Jan Maelwael, the “good painter”), born in Nijmegen, Netherlands near the border of Germany. Some of the paint he applied is still visible on the sculptures mentioned above. His most impressive remaining work, a circular Pieta painting was once hanging on the Charterhouse wall, is now exhibited in the Louvre. He advised the Duke to hire the Limburg brothers, creators later on of the Tres Riche Heures prayer books for the Duke of Berry.

Photos above kindly supplied by world traveler Annelies van Zwol.

Additional photos found on Wikipedia.

Further reading:

Bart van Loo: The Burgundians, A vanished Empire.

Frits Scholten, ‘Claus Sluter eindelijk in Nederland’ in: Rembrandt Bulletin, summer 2021. Vol. 31#2, pp. 26-29.